Commission History

Connecticut General Assembly

The Connecticut River Gateway Commission at Fifty

A unique conservation compact looks to the future

By Judy Preston, first appeared in Estuary Magazine, Spring 2023

It takes the vigilance of every generation to protect a valued natural resource, like an estuary. One generation rarely remembers, or can even imagine the threats of another’s as time and technology progress. It wasn’t that long ago — 2014, that the specter of a new railroad bridge across the Connecticut River at its mouth was unveiled to address “cascading delays to rail and maritime traffic.” In 1996, it was a proposed regional sewage treatment plant. In 1974, it was the potential for an oil refinery for Long Island Sound to be located in the town of Old Saybrook. The idea of a bridge connecting Connecticut at the river to Long Island, New York, dates back to the 1930’s, with comprehensive plans developed in the 1960’s and 70’s.

Each of these threats were met in their day by the individuals and communities that rallied to raise awareness and seek alternatives to the plans that could forever change the extraordinary natural intactness and beauty of the Connecticut River estuary. It is a place that has both withstood and helped define the human communities that surround it.

But it was a proposal to create a National Recreation Area along the entire length of the Connecticut River in the early sixties that ultimately catalyzed people to think about the River as a common asset. And in the estuary region — labeled “The Gateway” on the federal planning maps that divided the watershed into three sections — a unique idea took hold.

That was fifty years ago. Spoiler alert: the federal plan was resoundingly defeated. But what remained after all the public hearings was an idea, and an ideal, for a partnership for natural resource protection that was ahead of its time. In a small northeastern state with 169 towns, where land use is a complicated and often cumbersome tangle of federal, state and municipal regulations, towns ultimately cherish their local rule. What emerged from the original idea of national oversite of New England’s largest and longest river ended up, in the estuary, as a uniquely local compact to work together.

Great Blue Heron, Tanisha Bergeron

In the Beginning

In 1965, on a tour of the lower Connecticut River, then US Secretary of the Interior, Stewart L. Udall, a national advocate for environmental stewardship, noted: “We have a chance here to do a model job of conservation.” He had been invited by Connecticut’s Senator Abraham Ribicoff.

This invitation came despite, or perhaps because of the fact that the water quality of the Connecticut River had been described, in that same year, as “the world’s most beautifully landscaped cesspool” by another Connecticut notable, Katharine Hepburn.

Two years earlier Senator Ribicoff had acknowledged the river’s condition at a key conference held in Hartford by the U.S. Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare by noting that “Stretches of this once proud river now bear as its official classification: ‘Suitable for transportation of industrial wastes without nuisance and for power, navigation and certain industrial uses.’”

The state was already well aware of this: in 1966, a Clean Water Task Force was appointed by then Governor John Dempsey, which resulted in adoption of the state’s Clean Water Act of 1967. This landmark legislation was the first of its kind in the nation and was ultimately used as a model for the nation’s Clean Water Act, that didn’t become law until 1972.

River Conservancy

When Secretary Udall returned to Washington he brought his enthusiasm for the focus on the Connecticut River, and the following year Congress authorized a study to determine “the feasibility of establishing all or parts of the Connecticut River Valley from its source to its mouth...as a... National Recreation Area.”

In July of 1968 the recommendations from this effort were issued through the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation’s Northeast Region, formerly within the Department of the Interior, in a report titled New England Heritage. It identified 56,700 acres, covering 92 units of town government from Connecticut to the Canadian border, to be included in a new National Park through the heart of New England, “…as the nucleus of a revitalized conservation and recreation program for the entire river valley.” In Connecticut, this included the proposed federal acquisition of 4,100 acres, with the state donating 1900 acres. In the Gateway Unit, on the lower river, 23,500 acres of land that included river frontage and adjacent uplands were to become part of the National Park.

The Bureau of Outdoor Recreation clearly placed emphasis on recreational opportunities, citing projections of dramatically increasing participation by the year 2000. Its report stated: “The landscape and waterscape of the Connecticut Valley must be called upon to satisfy portions of the region’s needs for additional recreation opportunity”, concluding that “Presently undeveloped resource areas will have to come into play.”

One by one the towns up and down the Connecticut River where the new National Park was proposed registered their concerns. In Connecticut, public hearings were held in Essex, Middletown and Hartford. As the details of the proposal became known, the implications of a full scale National Park facility began to sink in: access roads, reception centers, camp-sites and picnic grounds, with an attendant concern for, among other things, “…a trail of empty beer cans, litter, and other trash.”

Eight years after the concept was introduced it was rejected by all four New England states involved. Many reasons were cited for the failure, but in particular the dramatically condensed timeframe for federal evaluation of the concept. The feasibility study authorized by Congress was from October 1966 to mid-1968 — less than two years for investigations, formal hearings and detailed plans for four states.

Perhaps most critically, Gregory Curtis (who would be key to keeping the idea of a version of the proposal alive in Connecticut) later wrote that the lack of local and even state input into the process, which might well have changed the emphasis of the national park proposal from urban recreation to preservation early on, and the predetermination of Congress that the project be based on the “need for urban recreation” were critical flaws that lead to the ultimate demise of the National Park concept.

Gateway Advisory Committee

Undeterred by the rejection of the four-state initiative, and adopting the formerly proposed southern unit name from the National Park plan, Senator Ribicoff appointed an ad hoc Gateway Committee to explore an alternative in Connecticut.

For in its opposition, the towns along the lower region of the river — it’s estuary — had come together in their opposition and realized that they shared a common idea: the Connecticut River defined their towns. Gregory Curtis, a retired agricultural extension agent for Middlesex County, became chair and William G. Moore from the town of Lyme became vice-chair. These two men were instrumental in doing what the national effort had been unable to do: to engage the local communities to weigh in on an alternative.

By reviewing the former plan, the committee identified two major concerns and concluded that any effort going forward would need to have controls and safeguards to protect the values that local residents believed unique to the region, and a means for “a strong valley voice” to determine the boundaries and policies that would oversee the proposed area.

There was a strong consensus for conservation and preservation of the area, while recreation was dropped, citing the existing popularity of the river for that purpose and concern for excessive use. Visibility from the vantage point of the river, and the protection of those ‘viewsheds’, was also an important consideration. And the estuary towns wanted to retain control, with back-up from the state.

In 1967 Senator Ribicoff quoted William Holly White, saying that “unless steps [are] taken to protect this resource [the Connecticut River] it could easily turn into a marine version of the Berlin Turnpike.”

A new browser window or tab will open to the RiverCOG website when you click to view the map. To return to the Gateway Commission website, look for your previously viewed window.

Judy Preston

The Connecticut River Gateway Commission Is Born

It was incoming state senator, Peter Cashman, who worked with William Moore and the Gateway Committee to craft a new plan. The “Cashman Bill” called for creation of the Gateway Conservation Zone, where conservation and preservation remained front and center while both recreation and the concept of eminent domain (part of the initial federal plan) were discarded. The area of the Conservation Zone was slimmed down, and land protection — considered key to preserving the natural beauty of the river, would be accomplished through development rights and scenic easements.

Ultimately the Connecticut River Gateway Commission emerged from the efforts of the Gateway Committee, created to protect “The unique scenic, ecological, scientific and historic value” of the estuary region, and “prevent deterioration of the natural and traditional river scene.” In 1973, through an historic piece of legislation entitled “An Act Concerning the Preservation of the Lower Connecticut River” a one-of-a-kind compact emerged to oversee and protect the estuary — the Gateway of the Connecticut River. State historian and local resident Ellsworth Grant wrote, “In probably the nation’s first such regional conservation agreement, eight Connecticut towns have joined hands to protect the banks of the river through local control backed by the state.”

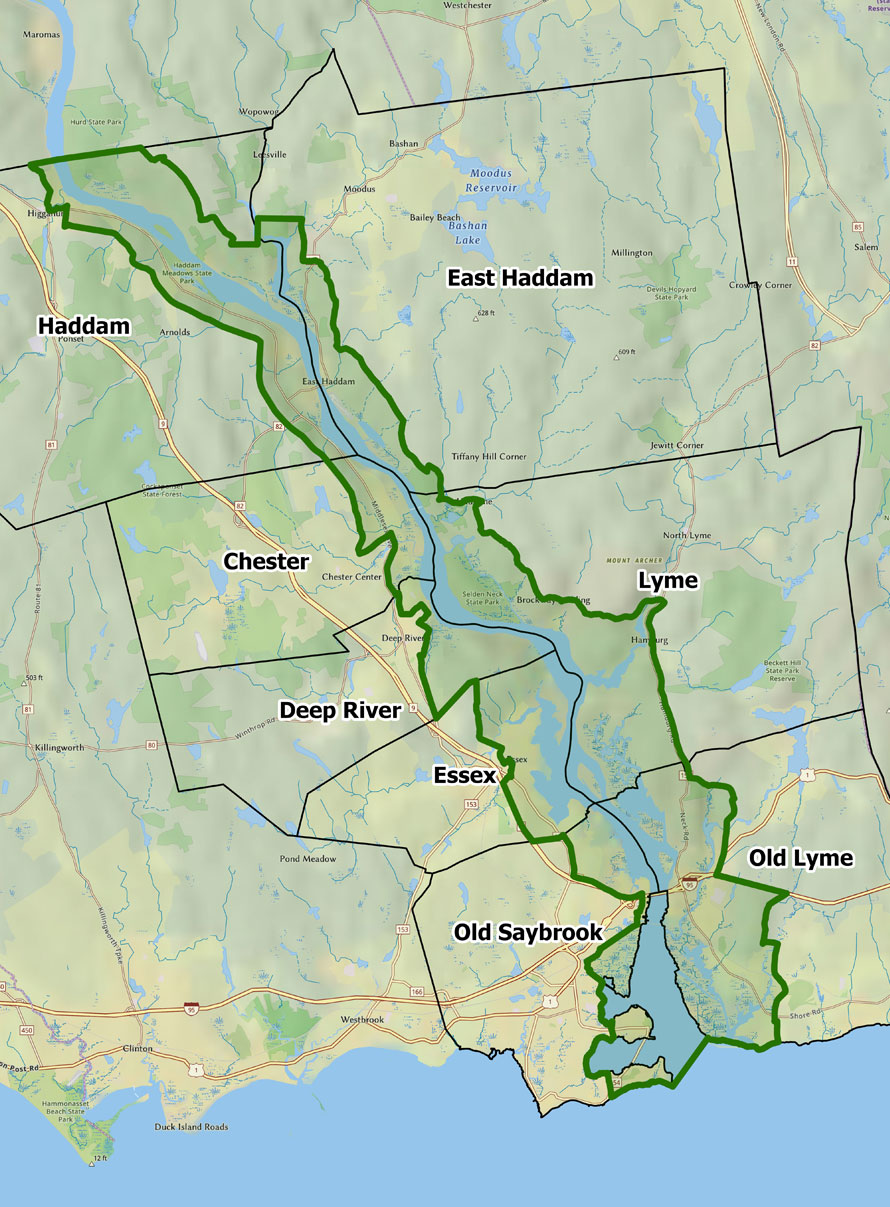

The Commission would be officially established only when at least five of the eight lower river towns — East Haddam, Lyme, Old Lyme on the east bank, and Old Saybrook, Essex, Deep River, Chester and Haddam on the west bank — voted at town meeting to join the compact. All eight towns voted to join. In addition to the town representatives, there would be two regional positions, one from each of the two regional planning agencies covering the lower river towns, and a representative of the Commissioner from the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), now the CT Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CTDEEP). With the exception of the state liaison, and a support position from the Connecticut River Estuary Council of Governments (RiverCOG), all members of the Commission are volunteers.

The Gateway Mission: “…to preserve the aesthetic and ecological natural beauty of the lower Connecticut River valley for present and future generations….”

Originally the Cashman Bill authorized a bond issue for $5 million dollars to acquire 2,500 acres of scenic easements and development rights in the Gateway Conservation Zone. Although this did not materialize, in 1982 a settlement agreement with Northeast Utilities resulting from the visual damage caused by the construction of overhead power lines across the river between Haddam and East Haddam generated a one-million-dollar endowment for the Commission.

Fifty years later: The Gateway Commission today

The Gateway Commission operates within a 21,500-acre Conservation Zone which encompasses the Connecticut River estuary, its shoreline and the landscape up to the first ridgeline. Its toolbox includes regulatory zoning standards, land protection, and education.

Gateway’s impact comes in part through its ability to influence zoning standards as a tool for protecting the visual, including scenic and historic, qualities of the lower river viewshed.

The Commission establishes zoning standards that focus on building height, setback, lot coverage, and protections for vegetated buffers, that each of the member towns adopt and enforce within the Gateway Conservation Zone.

The Commission both reviews and acts on applications that are referred to it by each town’s land use boards.

“In probably the nation’s first such regional conservation agreement, eight Connecticut towns have joined hands to protect the banks of the river through local control backed by the state.”

— Ellsworth S. Grant

No zone change, or change in regulations affecting land within the Conservation Zone, can become effective without the Commission’s approval. This is not a widespread authority in Connecticut and is part of what makes the Gateway Commission unique.

Land protection was initially envisioned as donations and acquisition of scenic easements that would be transferred to the state. With the benefit of the Northeast Utilities settlement, land protection efforts now include negotiation for fee acquisition and partnerships with other land protection organizations working in the estuary region. The Commission also today offers matching grants to seed local fundraising efforts for land protection.

Since its inception, the Gateway Commission has protected 1,100 acres of land in all eight River towns in the Conservation Zone, working with land trusts, conservation organizations, towns, and the state. Most recently this has included a matching fundraising grant to the Old Saybrook Land Trust, funds toward the acquisition of the Roger Tory Peterson property in Old Lyme, and the purchase of a riverfront parcel in the Town of Chester. These investments in land protection in the estuary region have totaled over $2.3 million dollars to date. A new grant program has also been established to assist with local efforts to safeguard the scenic, historic, and ecological resources of the lower river.

Regulations and land protection are two important tools used by the Gateway Commission to accomplish its goal to protect the unique scenic, ecological, scientific and historic value [and] to prevent deterioration of the natural and traditional river scene. But without education that actively seeks to inform and inspire residents and visitors alike, the ability to protect this natural asset is diminished. To that end, and in celebration of its fiftieth year in 2023, the Gateway Commission has unveiled a new website to make available multiple resources: historic, ecological, information about grants, educational resources, and links to partner organizations.

The Road – and the River Ahead

The Connecticut River Gateway Commission remains today a resource-based, regional approach to the protection of natural resources that is grounded in the individual land use departments of the eight cooperating towns that safeguard the Gateway Conservation Zone.

Commission member Melvin Woody, from the town of Lyme, is the longest standing member of the Gateway Commission; his involvement goes back to its establishment in the early 1970’s. He is poignantly aware of the challenges that the Commission, and the estuary, face: ''People who come to live on the river come for the views and they are basically ruining it for each other.'' As the ridgelines continue to accommodate homes that seek the one-of-a-kind view of the Connecticut River and its marshes, coves and historic villages, the experience of the valley from the river changes, and loses what the Gateway Commission — and many of the River towns, seek to protect.

Riverquest

The “natural and traditional riverway scene,” as historically interpreted by the Gateway Commission, is that which existed when the enabling legislation in 1973 was established. At that time, large homes carved into the treed hillsides were largely absent. The visibility from the river was a guiding principle of the Cashman Plan.

Linda Krause, former Executive Director of the estuary’s first regional planning office (that was later consolidated into the more widespread Council of Governments for the estuary region — today’s RiverCOG) noted in the early 2000’s when the Gateway Commission amended its standards to, among other things, blend new structures with the existing landscape: ''It is not the size of the house, but how it is presented. This is in no way intended to reduce the ability to have a view. What it is intended to do is to show us the context and minimize the appearance from the river. Just try not to make it yell.''

Today’s newest visitors would hardly know that the estuary was once described as “the world’s most beautifully landscaped cesspool”, nor would, even five years ago, anyone have been able to predict the scale of the threat posed by the latest aquatic invasive plant species, Hydrilla. And as climate patterns continue to be disrupted, it remains to be seen how changes in precipitation — both rates and duration, sea level rise, and warming temperatures — will impact the lower Connecticut River.

Despite these existential threats, the estuary region, many of its headwaters, as well as Long Island Sound, to which it is inextricable linked, continue to persist and even in some capacity, thrive. They are, collectively, what continues to attract people to this part of New England. And it is the human component that is both the greatest threat, and hope for the estuary — indeed so many of the natural places that people value will only persist with human intervention.

Judy Preston

An Exception for a Landmark Building

The Goodspeed Opera House has prominently stood along the Connecticut River since the 1870’s. Now a noted theater, Goodspeed Musicals has sent 19 productions to Broadway and won two Tony awards. In recognition of the historic building and the surrounding village’s scenic quality, the CT River Gateway Commission and the East Haddam Planning & Zoning Commission collaboratively collaboratively developed unique zoning standards that included an exception for the landmark theater’s height.